Have you ever wondered if among the strangers you meet every day, there might be someone extraordinary—heroic even?

Glen Northcutt doesn’t have any super powers, but for more than 60 years, people have been calling him a hero.

You would think it would be easy to spot a hero, but when I first met Northcutt, he wasn’t wearing a cape or any of the usual hero attire. But he did have a smile on his face as he met me in his driveway, shook my hand and led me inside his home.

Everyday Hero

He seemed like any other normal person: kind, hospitable, ready with a joke or two. As we talked, he began to share his story with me, and I listened. I was hoping I could learn a little about what makes someone a hero.

As it turned out, Northcutt and Superman did have a bit in common: they both grew up on farms. But the similarities took a break there. After finishing high school, Northcutt decided the farming life wasn’t for him, so he left his home in western Oklahoma and enrolled in telegraph school in Colorado. Eventually, he became a Telegraph Apprentice for the Santa Fe Railway. After a transfer from Kansas, Northcutt wound up in Moore, Oklahoma.

Up to this point, Northcutt’s story seemed pretty average. Interesting and enjoyable to be sure, but I knew these weren’t the reasons so many people considered Northcutt a hero. Then, right on cue, Mr. Northcutt took a breath, the air grew still and he continued his story.

Saving a Life

On October 7, 1954, a freight train was heading south through Moore on the Santa Fe Railway. As a Telegraph Apprentice, part of Northcutt’s job was to watch the trains as they went by the depot to make sure there weren’t any problems. Northcutt had seen hundreds of trains go by, but this one was different.

Before he saw the train, he heard its warning blasts. He rushed outside to see what was wrong, and saw a six-year-old girl balancing on the tracks ahead of the oncoming train.

He didn’t think; he just ran.

The train had pulled its emergency brakes, but it was too late to stop. There were about 12 to 15 yards between Northcutt and the girl, and the train was closing fast. The girl, still oblivious to both the train and the man sprinting towards her, had no idea her life was in peril. The train, traveling just under 50mph, was only about ten yards from the girl, but Northcutt reached her first. He snatched her from the tracks and dashed aside as the train whizzed by in front of them. He had raced with a train and won.

What goes through your mind when something like that happens? Anything at all? I asked him.

“I was just worried she would look up at the train or at me, get scared and fall,” said Northcutt. “If she’d have fallen, I wouldn’t have been able to save her.”

The girl, Linda Sherwood, had been walking home from school.

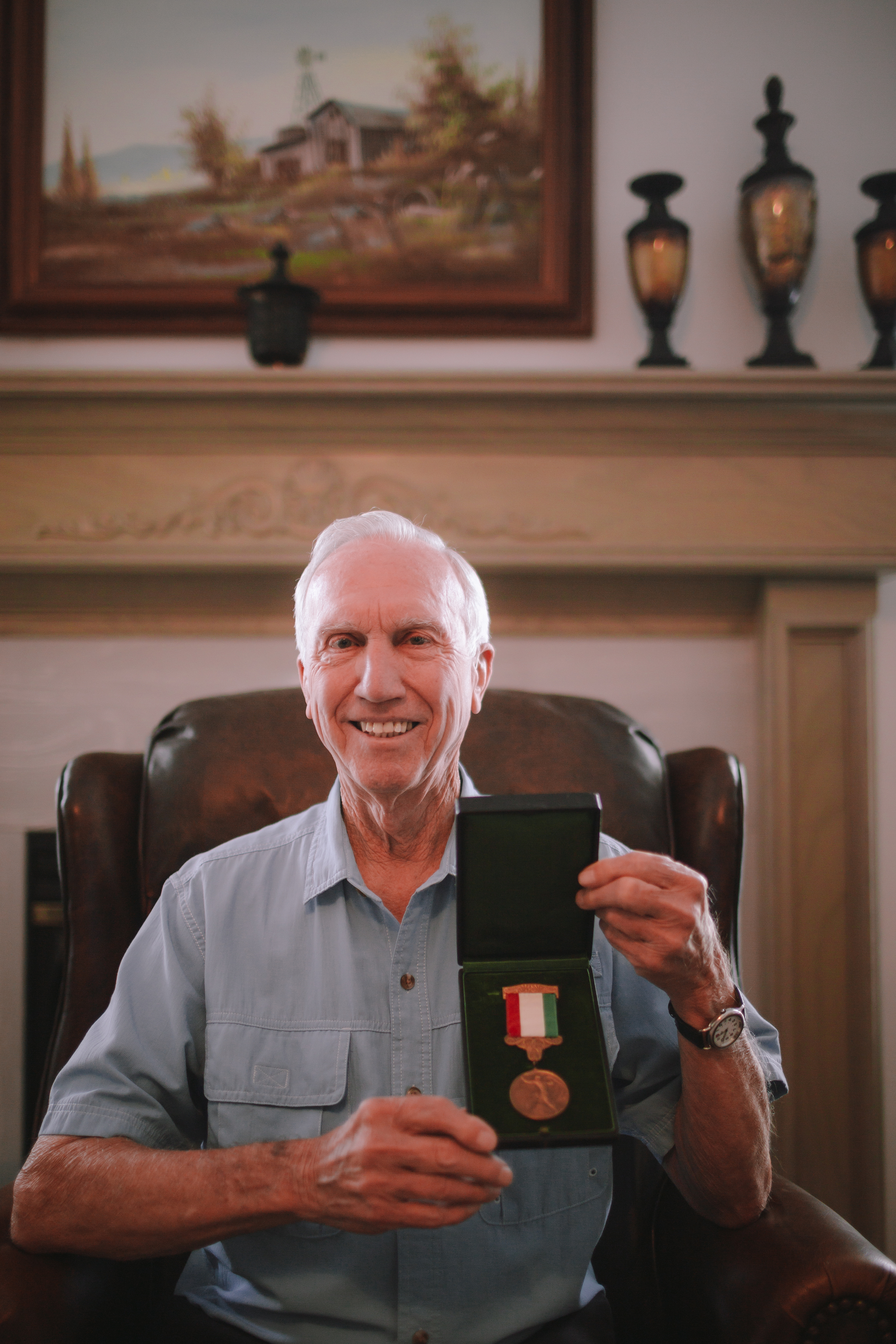

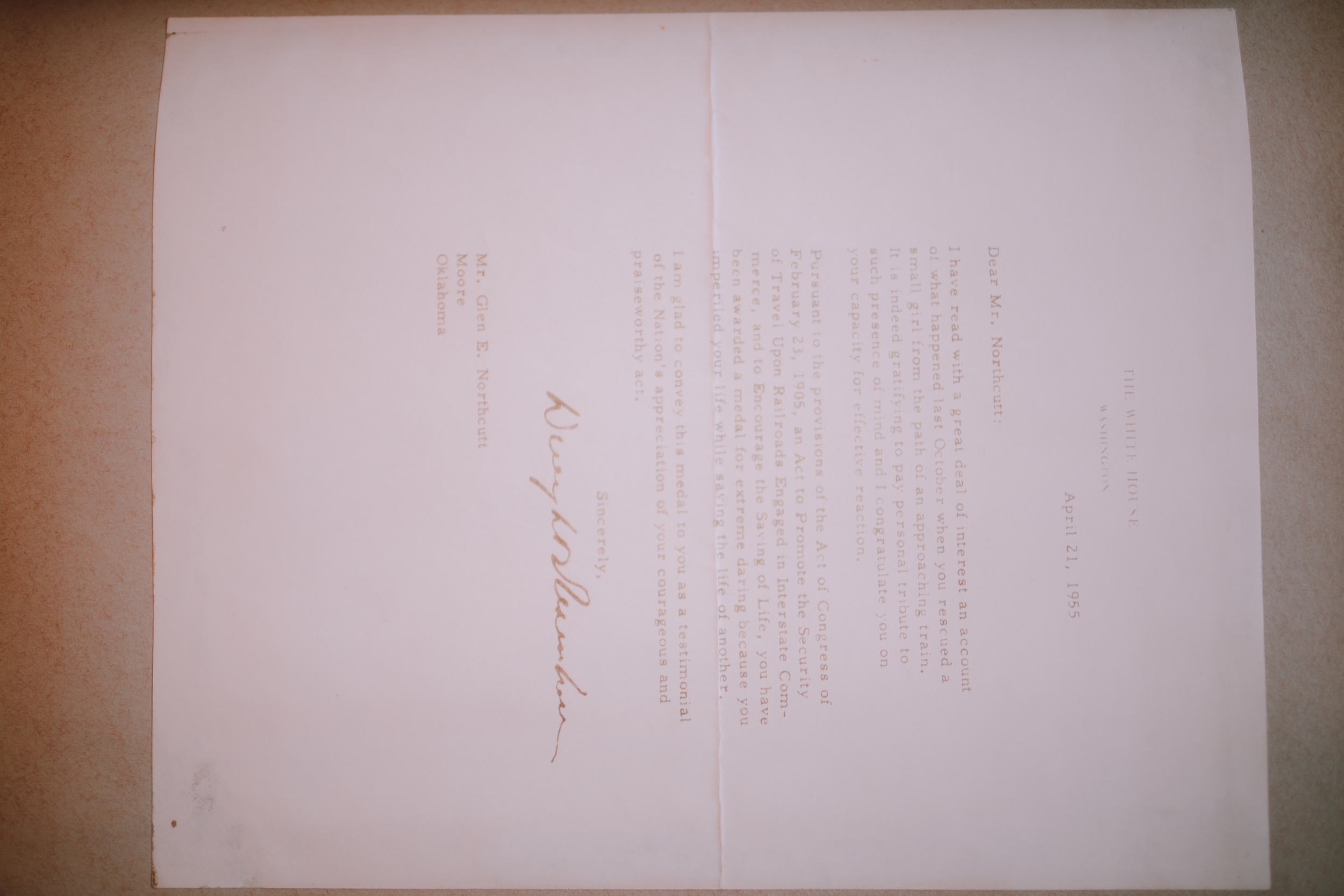

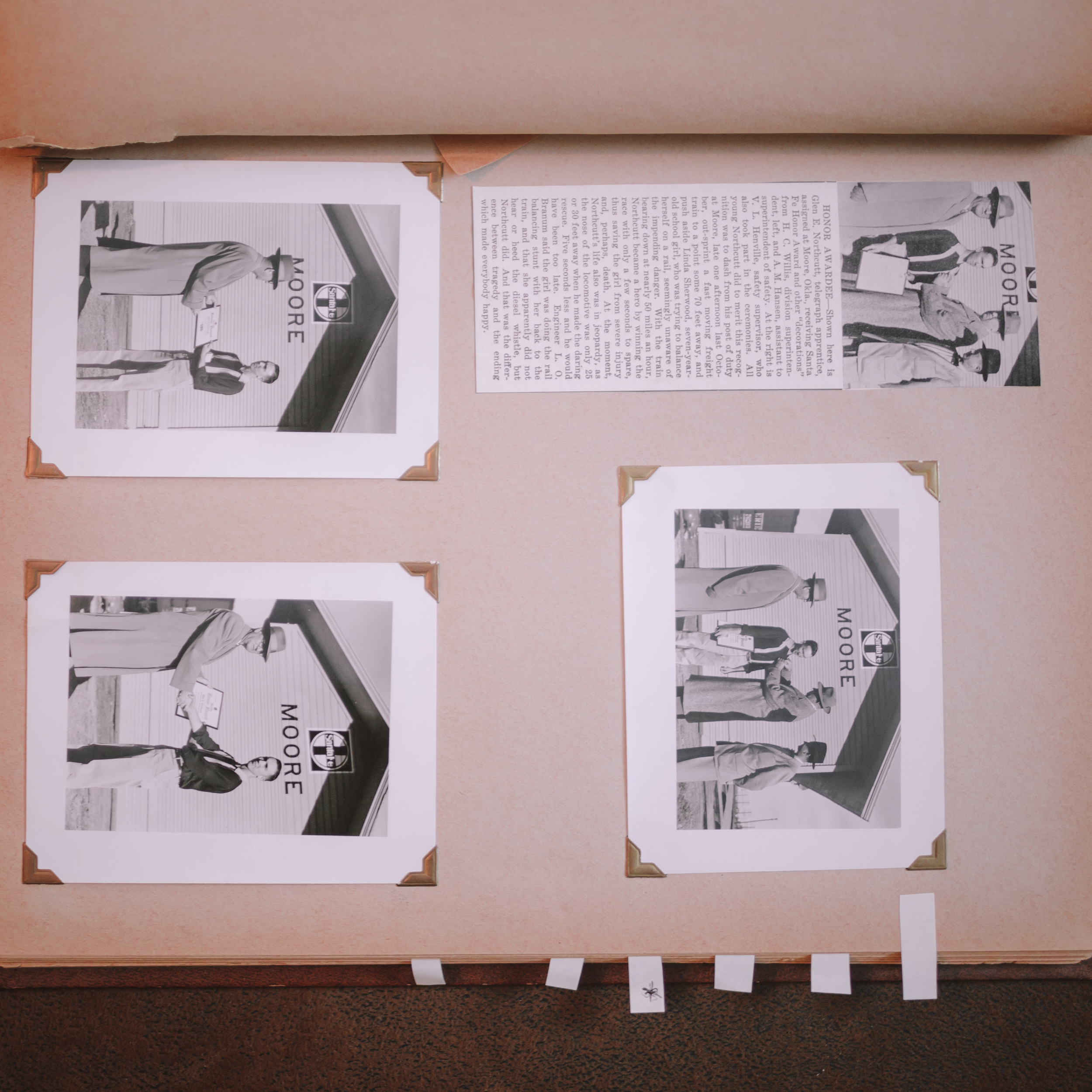

No one knew whether or not they were alive until they looked back after the train stopped, four blocks south of the depot. But it wasn’t long after that that thousands upon thousands were reading about him in the papers. Sixty-one years ago, in the July of 1955, Northcutt was woken up with the news that he would be going to Washington DC—he was to receive a presidential medal of honor.

Nationally Recognized

Northcutt chuckled to himself as he remembered going to get his tickets to DC and finding a host of reporters waiting for him. I asked him what he thought about all that fanfare, and he just laughed and said that “for an old cotton farmer,” it was something else.

Northcutt received a letter from the president; the Chairman of Interstate Commerce presented him with a medal (since President Eisenhower was out of the country) and he was invited by the Oklahoma Senators, Robert S. Kerr and Mike Monroney and also Congressman John Jarmon for a meal in the senate restaurant.

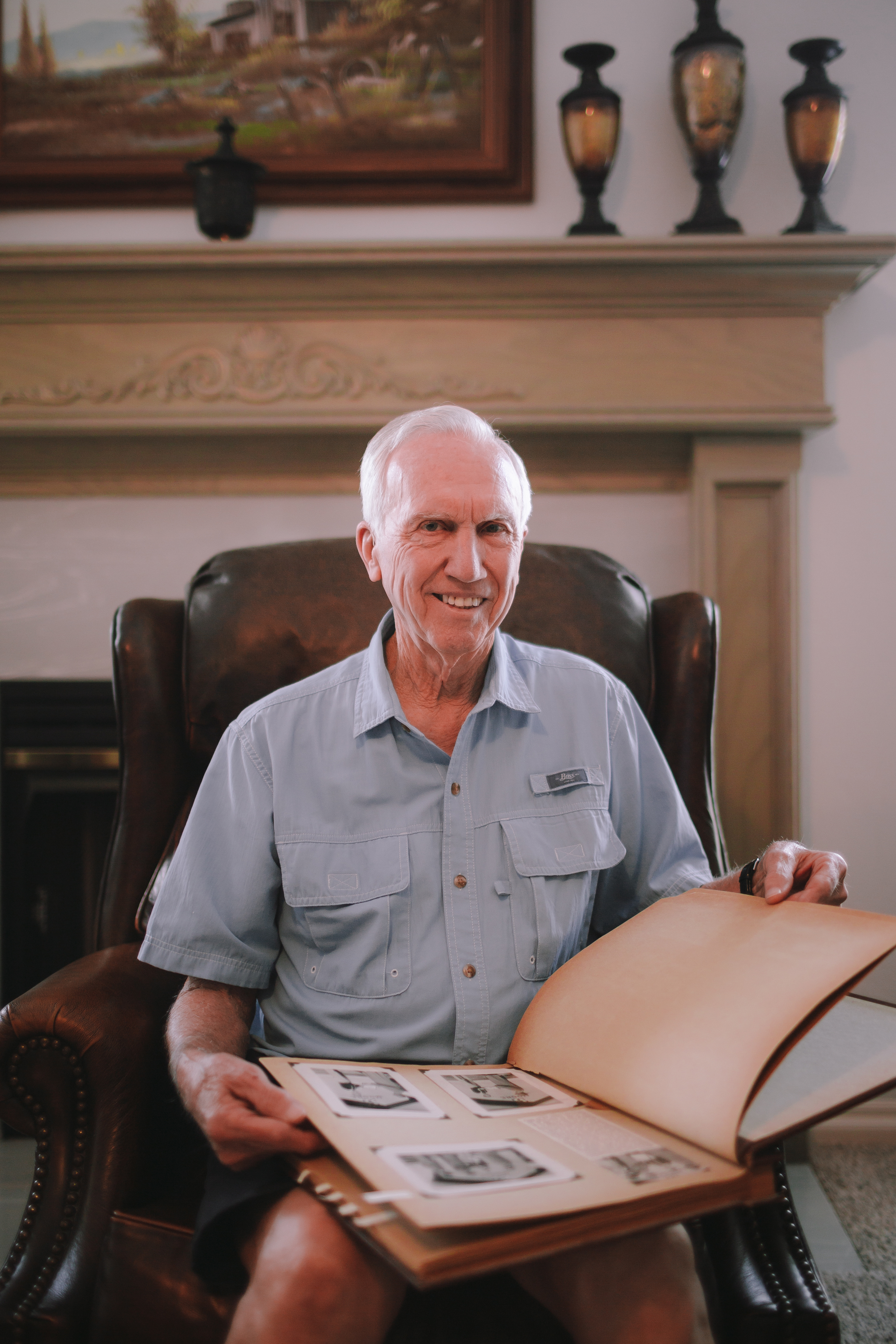

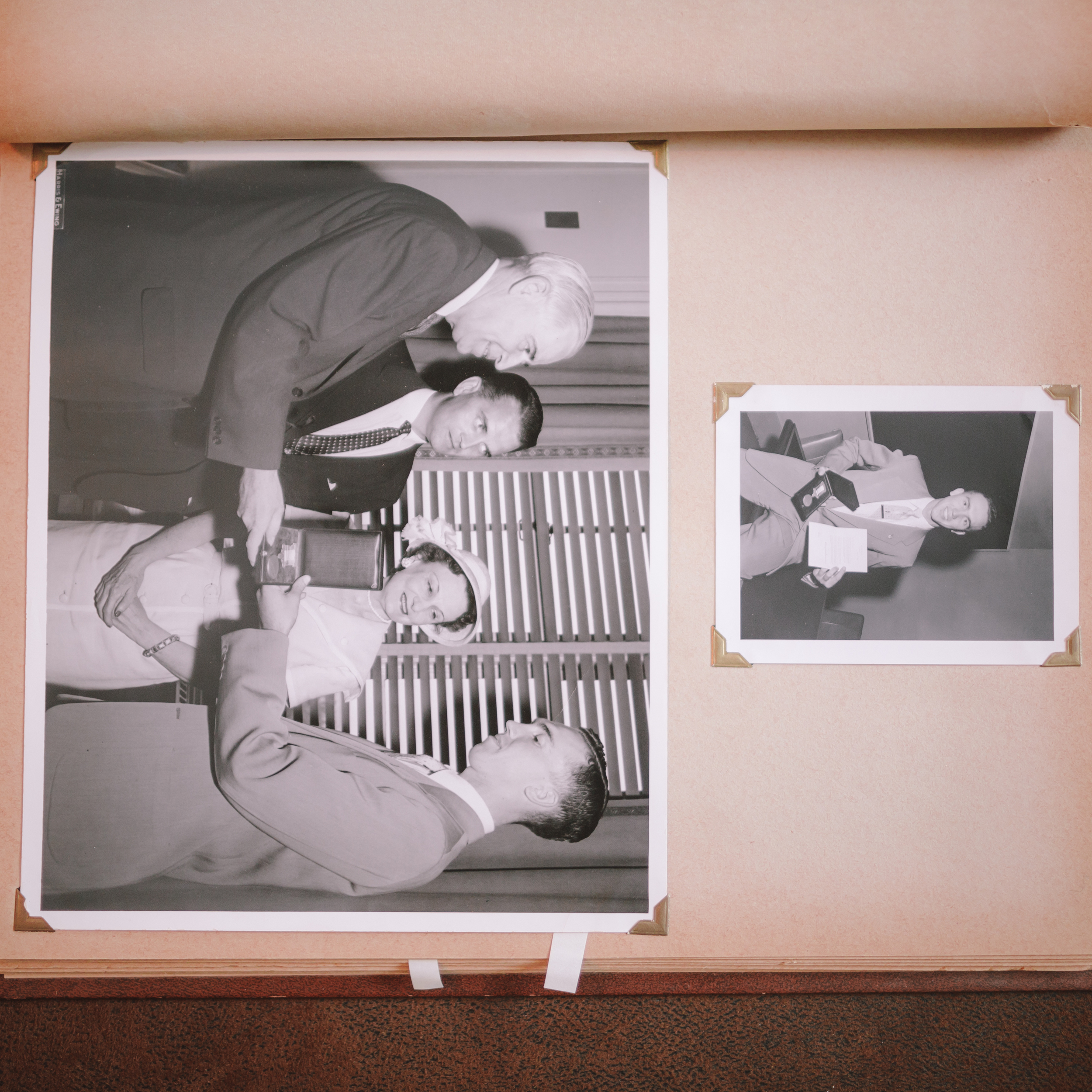

Northcutt turned the pages of a scrapbook, showing me the faded letter from the president, and the menu from the senate restaurant. Among other letters and pictures, the scrapbook had quite a few news clippings. Most of them had the word “hero” in bold as a part of the title. I asked him how so many people calling him a hero felt.

“I didn’t think anything about it,” said Northcutt. “Saving her was automatic. I didn’t consider myself a hero. I just did what needed to be done.”

At that moment, I began to wonder if being a hero was a lot simpler than I had first imagined it.

For many years after, Northcutt continued living in Moore. He served on the city council and the volunteer fire department. He worked at Tinker for over 31 years, married and raised a family. He lived a happy and fairly normal life. Now, Northcutt is 81 years old. Looking back on it all, he says “It’s something, through the years, you feel like you did accomplish something that’s the crown of everything.” Having had two daughters of his own since the event, he feels that if someone had done the same for one of his daughters, he wouldn’t be able to thank them enough.

As our time together was drawing to a close, I asked him if he felt like that one moment—saving the girl—had changed him in any way. He paused, thought for a moment and said “Not really. Not really.” I think, for Glen Northcutt, being a hero isn’t a distant ideal that only crash-landed aliens with super strength and laser vision can achieve. And it isn’t something that comes upon you in one moment of heroism. I think being a hero is at the core of him, and—maybe—at the core of each of us.